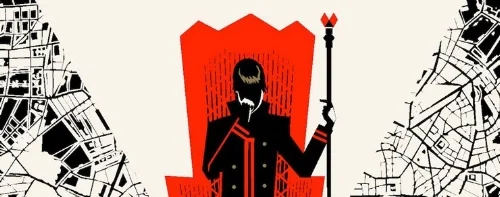

In this article for the British Association for Victorian Studies (BAVS) postgraduate blog, I offer an academic review of the New York Times bestselling novel trilogy, Shades of Magic by V.E. Schwab. The series, which reached its thrilling conclusion with the final novel, A Conjuring of Light, on February 21, 2017, is set in four alternate-history parallel-universe versions of London in the year 1819. Using research in nineteenth-century scientific discourse, readings of works by Mary Shelley and Bram Stoker, and recent scholarship in Victorian studies, I argue that Schwab’s novel invokes the language of early experiments in electricity and magnetism to configure both biological and spiritual ideas of life and death.

And, for fans of the series, I also offer my academic take (as someone writing a dissertation that came out of Dracula) on the whole "Alucard is Dracula spelled backwards" debate. Enjoy!